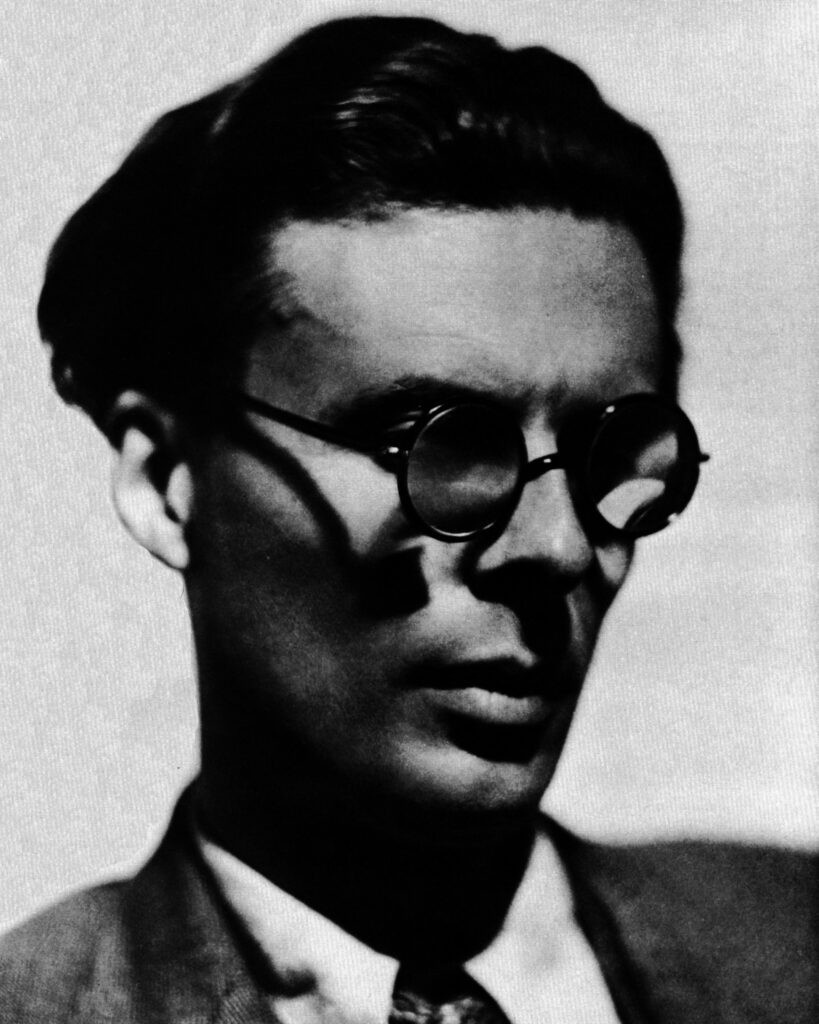

“One no longer must decide whether or not to use the propaganda weapon; one has no choice.”-Ellul, Propaganda: The Formation of Men’s Attitudes (P 134)

“In a battle between propagandas, only propaganda can respond effectively and quickly.”-Ellul, ibid (P 137)

Propaganda and Politics

Consider two examples from the 20th Century. First, the Russian Revolution of 1917— a situation in which propaganda was instrumental in the hands of Lenin and Trotsky. Second, in the molding of China into a Communist State, where propaganda was also essential to the revolution of Mao Tse-Tung. In order to determine how indispensable propaganda was to the two defining political events of the 20th century, the French thinker Jacques Ellul conducted a detailed study of both regimes. In his work, Propaganda: the Formation of Men’s Attitudes, Ellul made the following observation: had it not been for propaganda in the form of literature, and in the political action spurred on largely by propaganda (in the form of revolution) neither Lenin and Trotsky, nor Mao Tse Tung, could’ve achieved their respective goals. (P 288) Ellul, when writing in the 1960’s, analyzed the actions of leaders in communist countries (such as Russia and China), which he viewed as models where propaganda had been used as a source for exercising political power and influence. The guiding questions of Ellul’s inquiry rest on what makes the propaganda effective—Ellul was neither a moralist, nor a communist ideologue. He was concerned with the massified use of propaganda, as it took root in the 20th Century: as one witnessing its development, from the beginning. Ellul was not prepared to condemn a whole era of history. In the wake of Communist propaganda, Ellul leaves behind the prospect as to whether or not “it was true.” For, in the event of the communization of a country such as China, “the problem of truth or doctrinal persuasion is of no importance in the process.” (P 289)

Mao’s legacy begins right after the revolutionary actions of Lenin. The importation of Marxism-Leninism into China was integral for bridging the gulf between Russian forms of

Communism, with that of Mao’s own distinctive understanding of Marxism. Mao was not a strict adherent to the ideas of Lenin, or the theoretical writings of Marx. Mao would appropriate the literature of Marxism, with the revolutionary movement of Lenin, into a force of his own. In his book, Ellul looks at the manifestation of Marxism in China, and the massive scale at which Mao implemented his project, as a staggering example of the power of political propaganda (which had hitherto been foreign to the East.) The force at which Mao’s own propagandistic strategies were employed, and used repeatedly, warrants the attention of any serious student of philosophy and history.

In the earliest stages of Maoist China, the combined forces of the propagandists were designed to be relentless—to leave the people, without a moment’s reprieve. Precisely because Mao Tse Tung considered his monumental task, as the new leader of China, to require nothing less than the re-molding of the Chinese people. This re-molding and transformation of China expressed itself in Mao’s ambitious strategies known as “The Great Leaps Forward.” Beginning in the late 1920’s, Mao employed various methods for the purposes of propagandizing the Chinese people: it required the early writings of Lenin, the organization of public schooling, the strength of the Chinese red army, as well as the development of peasant unions. When describing the methods of Mao, Ellul stated the following: “The objective of Mao’s propaganda is a double one: to integrate individuals into the new body politic […] and, at the same time, to detach them from the old groups, such as family or traditional village organizations.” (P 308) The project of Mao had to be totalizing: the deeply rooted tradition of Confucianism had to be supplanted with Socialism; the notion of filial piety had to be eclipsed by a loyalty to the Chinese Communist Party; the villages and communities on the margins of the new Chinese government, had to be infiltrated by officials of the Red Army, for the purposes of conditioning the peasants into an entirely new way of thinking. In every instance, Mao devised his propaganda, to pound, to alter, and remold the Chinese people, with the machine of propaganda—this could only be achieved by what Mao called “political mobilization.”(p 304) An absolute mobilization, spanning from the workers factories, to the military, down to the peasant communities—the lives of the people were to be inundated with, and nourished by the new communist values.

Mao’s Ascent in China

In the earliest stages of Mao’s ascent to power, he implemented the use of highly effective slogans, as his primary form of propaganda. It was imperative for Mao to organize people under such persuasive political maxims as: “Benevolence for the people, dictatorship for the enemies of the people.” (P 309) In order to establish a polarization between communist party supporters, and the dissidents, Mao created the Peasant Unions, who could then freely disseminate such slogans, and determine who the internal enemies of the people were. The major obstacle to Mao’s machine of propaganda came from the resistance of internal enemies, who required a strong guiding hand, at the efforts of Peasant Union officials. Had Mao not implemented the use of such unions, he could never have reached so many villages, groups, and communities, in his early years of political mobilization. (P 306) After all, the only limitation for a political figure of such great ambition is time. In conjunction with the Peasant Unions, another key component of Mao’s propaganda machine, came in the form of the Chinese Red Army. In Mao’s own words, “The Red army does not make war for war’s sake: this war is a war for propaganda in the midst of the masses.” (P 306) The soldiers of the red army were trained for fighting, in the traditional sense, yet, their primary function was to mature into full functioning propagandists; integrated into the masses, working alongside ordinary civilians. Again, a slogan expressed in poetic language was repeated often, “The army must function among the people like a fish in water.” (P 307) The soldiers were to vanquish their opponents, as covertly as possible. The Red Army generated soldiers and support, through sheer force and methods of persuasion. Under Mao, the Red army declared war on the ideals of antiquity, as well as any potential dissidents—often with terror.

Even with this threefold approach to devising propaganda (i.e. Mao’s own slogans and writing, the Peasant Unions, and the founding of the Red Army), the use of sheer force, was still necessary, to mold an entire nation. To demonstrate this point, Ellul writes: “Even a propaganda centered around education cannot do without terror. In order to arrive at full compliance with propaganda, the 7 percent of “incorrigible” individualists must be eliminated.” (P 308) The elimination of all internal enemies is what eventually followed. After nearly three decades of implementing the propagandistic machine of education, and mobilization, more cunning tactics were required of Mao and his representatives. In the year of 1956, a new phenomenon emerged, known as the “Hundred Flowers Campaign.” The promise of the campaign, with its apparently benevolent gesture, was one of democratic process, where all members of the society would meet for rational inquiry, freely expressing their criticisms of the Chinese Communist Party. In actuality, the campaign facilitated nothing resembling a democratic process. The end result was such that all the dissenters and opponents of the communist party had made themselves known, were now publicly exposed, and punished accordingly. These enemies of the people were imprisoned, and even executed. Mao justified his own tactics, employed during “The Hundred Flowers,” through the use of poetic flourish: “the rectification campaign [could not] be gentle as a breeze or a summer rain for the enemies of the people.” (P 308)

Perhaps the motivations of Mao can be elucidated, by considering his general view of human nature. Mao interpreted the human being as a malleable creature, who could have ideologies, and propaganda impressed upon him. This means that man was neither a rational animal, in the classical sense, nor the benevolent character of the moral idealist. Mao could begin with man as a manipulable being, that he could subject to political experimentation. This meant both that the common man and the State would be jettisoned into Western standards of speed and efficiency. To achieve his grand vision, it demanded that he accelerate China’s economic growth, as readily as he accelerated the education and re-molding processes of the general Chinese civilian.

When explaining his theoretical outlook, in a report of 1957, Mao stated: “When one builds a socialist society, every person must be placed in the mold […] We ourselves are being placed in the mold every year . . . I have gone through a re-molding of my own thoughts . . . and I must continue” (P 310)

What are The Limits of Propaganda?

In light of Mao’s own era of political rule, it becomes difficult to doubt the efficacy of propaganda, and how it can exert its influence on entire populations. Perhaps the notion that one is able to resist the propaganda of one’s own country, by escaping the mold, is a thought entertained only by naive westerners. Particularly, citizens of the more affluent societies, who’s own field of activity is limited to the world of consumption, and occasional voting; at the same time, comfortably supported by a modern liberal democracy, with little or no direct participation from individual voters. Along with Ellul, I am deeply skeptical about the theorists who argue against the efficacy of propaganda; as though one could be immune to political propaganda, sociological propaganda, and even to the uses of advertising. For citizens of England, Deutschland, and the United States (who live under liberal democratic rule) the basic freedoms

experienced in their daily lives has the potential to distort and/or limit their understanding of the customs of foreign countries, and the operations of international politics. In the time of Mao, people may have been forced to be free (to use a paradox from Rousseau), via aggressive tactics, and countrywide mobilization, which might be viewed as anathema to citizens of a liberal democratic type. However, the illusions of freedom one commonly enjoys, can cloud one’s judgment. Since the majority of Westerners are not forced, coerced, or molded into a type of citizen, they are scarcely aware of the subversive influence of propaganda, as it is disseminated through modern technology. Ellul warns against this naive notion (what he refers to as an illusion of today) namely, that those in affluent societies believe that technology can make them more free.

After reading Ellul, The word propaganda takes on a new significance. Ellul reminds us that the propaganda of the last century is dependent upon mass media. This is how it disseminated effectively; this is how leaders and propagandists are able to reach the public sphere, so forcefully. The more invasive a role propaganda can play, in the life of a citizen, the greater the potential for forming his attitude. This is to say, in how he votes, how he consumes, and how he thinks. Following Ellul’s own analysis of propaganda, the quest to separate the distorted data one is daily subjected to, from the undistorted information, becomes almost impossible. For, as I first mentioned in this essay, Ellul claimed, the problem of truth is often discarded, at the hands of the propagandist. “The Truth,” is replaced by mere “Means.” The effectiveness of propaganda, as a totalizing influence on society, becomes the concern of the propagandists. The content must exert a powerful force upon the individual. It should leave one with more questions than could possibly be answered, and lead to their being agitated, rather than relieved.