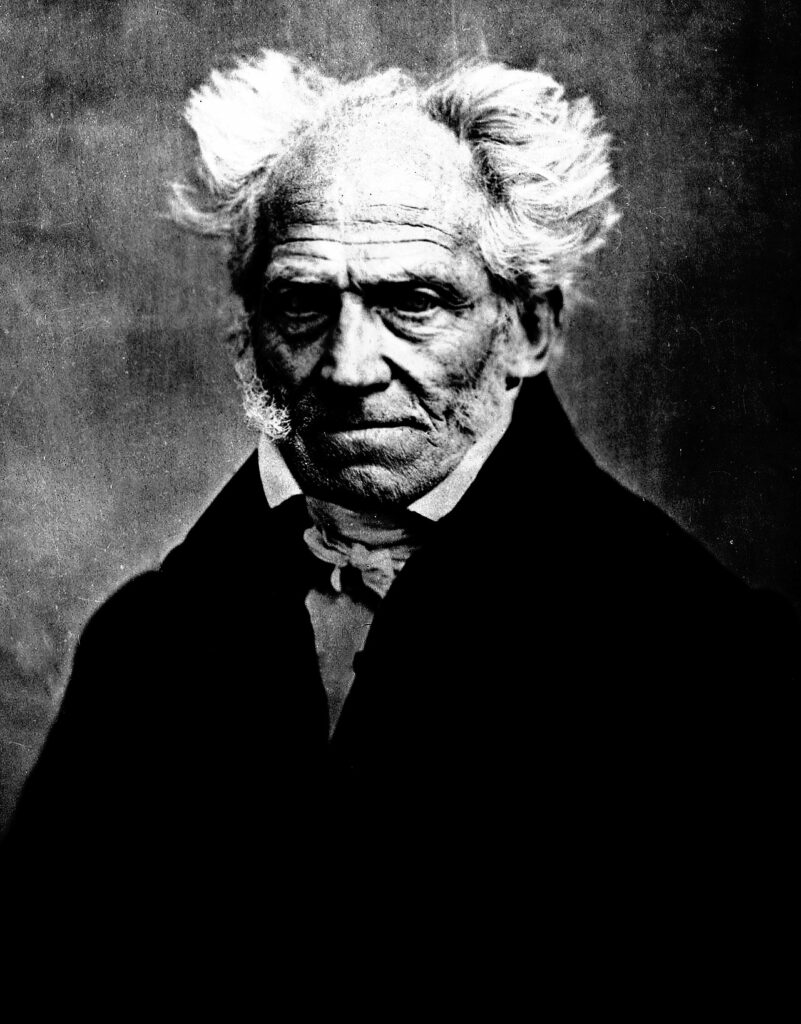

For a brief period, during the formative years of the young Schopenhauer (1813-1814), he and Goethe met for philosophical dialogues. These two geniuses of Germany had been acquainted by the efforts of Schopenhauer’s mother Johanna, who had hosted Goethe at her home, on various occasions. Schopenhauer had been an admirer of Goethe (as many of the youth of his time) since his days as a schoolboy. How impactful Goethe was on the ‘pessimistic philosophy’ of Schopenhauer (systematically developed in later years) remains an open question. However, the direct influence of Goethe on Schopenhauer’s writings can be seen in his own response to Goethe’s Farbenlehre; which, was written by Schopenhauer just a few years after the seminal work of Goethe had surfaced. In addition to Schopenhauer’s response to Goethe’s Farbenlehre, we can also learn that when the two met for philosophical dialogues, both men were at the time deeply engaged in readings of Indian philosophy and literature.

As the teachings of the East had recently been introduced to the world of the West, Schopenhauer and Goethe now had the pleasure of studying Hinduism, Buddhism, and essential texts (such as the ‘Mahabharata,’ the ‘Dhammapada,’ and the ‘Upanishads.’) The immeasurable value Indian thought added to the philosophy of Schopenhauer is well known (in the great praise given to the Indian tradition, by Schopenhauer in his published writings.) What is most intriguing, is to speculate as to how Indian philosophy impacted the respective lives of these figures; specifically, as to how it resonated with Goethe and Schopenhauer, during those moments the two were engaged in dialogue. Perhaps both Goethe and Schopenhauer compelled each other to write at greater length, and with greater devotion, on the significance of Indian thought, as it had so profoundly made its way into their own lives.

In the immediate years following the meetings of 1813-1814, Goethe completed poetry influenced by both Persian and Indian thought; Schopenhauer, spent four years developing his magnum opus: Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung. While Goethe developed his own theories regarding natural science, Schopenhauer ventured into the territory of metaphysics. Goethe flourished by bringing the lens of a gifted poet to color theory, botany, and physics; Schopenhauer’s audacious philosophy further germinated through his studies of Plato, Kant, and the Indian traditions.

By 1818, Schopenhauer delivered the manuscripts of his ‘self-proclaimed’ masterwork to the publishers. Even if Schopenhauer’s philosophical magnum opus was largely ignored until decades later, Goethe (with a foresight only he possessed), already proclaimed the genius of Schopenhauer, in prior years. As a result of Goethe’s first hand encounters with the young philosopher, he was right to predict that Schopenhauer would be revered one day; perhaps, even surpassing all others, in the field of philosophy.

In 1819, Schopenhauer and Goethe met, after a long hiatus. It is reported, in the correspondence of Goethe, that the two were “growing distant from one another,” which, may have been unavoidable, considering the ascetic nature of Schopenhauer, and the highly sociable nature of Goethe. Schopenhauer would continue to affirm himself as a lifelong student of Goethe, through the various quotations he included in his published writings, and in the ‘modest’ comparisons he made of himself: “as equal to that of Kant and Goethe.” Goethe also looked upon his ‘unofficial pupil,’ favorably; it is reported that he read Schopenhauer’s magnum opus with great enthusiasm. The reverence each man held for the other is clear. After only brief periods of interaction, the two would continue to cherish their relationship from afar. In both cases, the poet Goethe and the philosopher Schopenhauer, provided novel interpretations in all their research; at the same time, they produced literary as well as philosophical writing, which continues to reach far beyond the confines of academia, professional philosophy, and the era in which they first emerged as thinkers.