“Happiness on earth would be to die with pleasure in pleasure… The rest is nothing, it is fear that we dare not confess, […] the truth of this world, it is death.”

— Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Journey to the End of the Night

“The Word became flesh and dwelt among us.”

— John 1:14

CREATION

I await the coming of God in deep silences, with the regret of my sins—the greatest of them: to have been born. I await within me a spiritual, religious experience suspended between anguish and guilt. I call myself, before anything else, guilty of original sin.

In this sense, no human being is able to observe the moment when love is consummated inside the mother during the sexual night, of which we will later be the result. There is no visible figure for us; it is what Pascal Quignard would call the image that we lack, and what psychoanalysts call the Urszene. We are the result of a not-knowing, of a paradisiacal expulsion which was, in the beginning, the loss of union with Eden and, in turn, the separation from the mother. The image of God is missing, and it will remain absent, possibly until the day of my death.

SIN, THE CONDITION OF BEAUTY / JOY IN THE FACE OF DEATH / THE PLEASURE OF DYING

Is sin original or hereditary? The answer is diffuse, like a distorted image. However, the human being lies conditioned to a spiritual duality, because there is something divine in each one of us to the measure that there is something diabolical. The symbolic and sacred order of a society is possible thanks to the good–evil dichotomy inherited from Western tradition. Water, blood, sacrifice—these are elements that keep the human being purified of his evils.

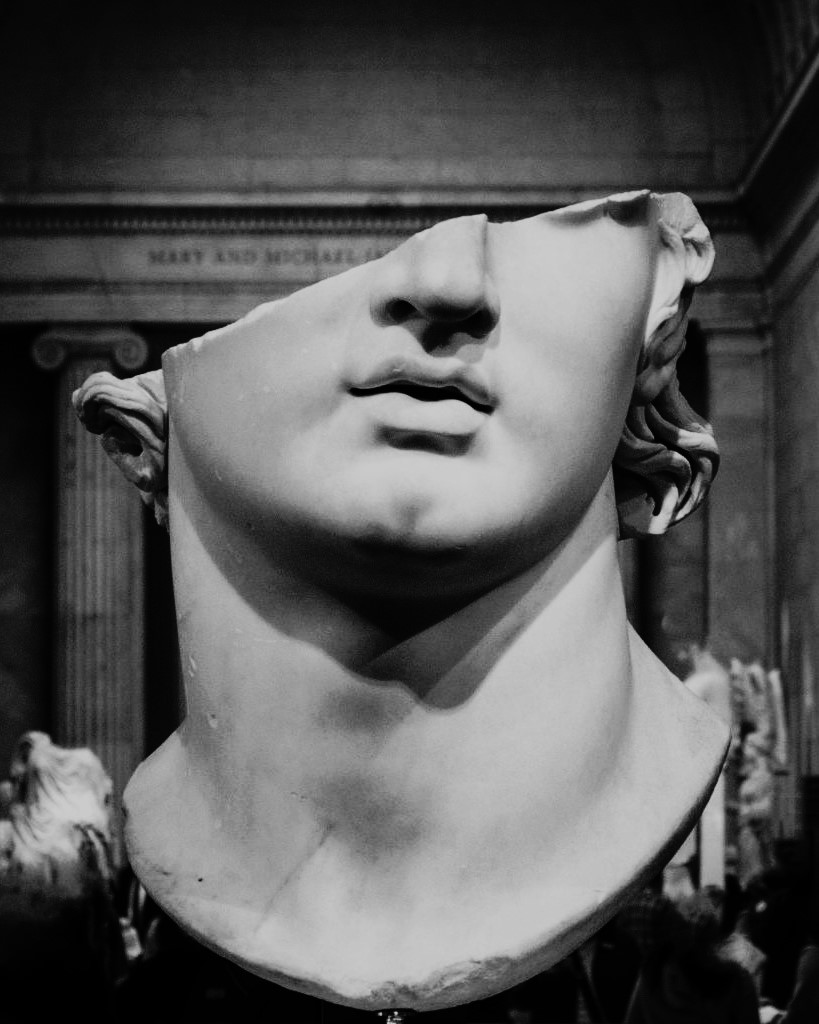

I remember, very distantly, two images that coincide with my thoughts and reflect death as an approach to the divine.

Firstly, Saint Teresa speaks of this religious ecstasy in her poem I live without living in me, in which she is a prisoner of the condition I die because I do not die—a vision that Bernini would later immortalize in sculpture, showing the union between the earthly and the divine. Saint Teresa is suspended, her face filled with plenitude, her lips slightly parted, her hand falling gently into the void, wounded with an arrow of Eros that has pierced her chest—symbolizing the love-union with God. This condition is an experience called the little death, known in French as petite mort, which alludes to orgasm—an instant where the being is neither alive nor dead, but in suspension, in ecstasy.

The second image, which has been the subject of study for various writers and represented in novels such as Rayuela by Julio Cortázar and Farabeuf by Salvador Elizondo, is the series of photographs of the Chinese torture known as death by a thousand cuts (in Chinese, Ling Chi or Leng T’ché). It depicts the torture of the murderer Fu-Tchu-Li, guilty of the assassination of Prince Ao-Han-Ovan, a punishment dating from the Manchu dynasty. The characteristic of this torment is that the victim experiences every pain without bleeding to death instantly—in other words, a slow death.

What is remarkable about this photograph is the peculiar way in which Fu-Tchu-Li serenely experiences his punishment, similar to Saint Teresa. Both seem to have reached an ecstasy between life and death—an encounter with the divine. For Fu-Tchu-Li, sin was the path through which he was able to approach divinity.

Julia Kristeva mentions: “Sin, on the other hand, is a state of fullness, of abundance. In this sense, it is transformed into living beauty […] the Christian conception of sin also implies a recognition of evil whose potency is proportional to the holiness that designates it.”

Joy in the face of death implies a union with the divine. Nietzsche says that when a god believed himself to be the only one, the rest died laughing. The gods died laughing—and with them died laughter. What remained, once again, was violence.

TEARS / CRUCIFIXION

The human being is an animal that cries from seeing how much is done in the name of God.

I write in the moment of not-knowing, where the soul becomes spirit, when memory becomes oblivion. I lose my identity and draw closer to the divine—in sadness, in lamentation, in weeping. At the moment of my death, I die of asphyxiation in the drift. Humanity is condemned to its misery, to its vanities. Vanitas vanitatum et omnia vanitas.

God is sad. God himself says he is sad. Tristis est anima mea. But God doesn’t just say he is sad—he says that he is so disgusted with life that he has gone so far as to dream of dying. He says that his soul is so sad that he feels like not existing. Then God repeats: “My soul is sad because I have reached the point where I desire death.”